It’s before sunrise and I’m doing some accounting while listening to conversations on Clubhouse. On the app, people can schedule and host audio chat rooms, or they can listen in the audience of someone else’s room and ask to speak on the stage by raising their hand. It’s the days following the Atlanta-area mass shooting, and we’re assembled in a #StopAsianHate room in solidarity and with empathy, acknowledging the rise in anti-Asian violence since the pandemic began. At peak times more than 1,000 people from around the globe are in this room, a testament to how rapidly Clubhouse is spreading. While it’s still invite- and iOS-only, tech incumbents are taking notice. Mark Zuckerberg has appeared on the app and is rumored to be developing a clone. Twitter has released its own Clubhouse-inspired voice-chatrooms feature called Spaces. People enjoy the way a real-time audio chat room gives their voice a platform. But as social media moves towards real-time voice, I worry that the millions of Americans who are like Joe Biden and Elon Musk will be silenced.

More than 19 million Americans have a speech, language, or voice disorder, with about 3 million of those having a stutter. Most people who stutter begin doing so between the ages of 2 and 6, and 25 percent of them stutter for life. People who stutter can be mistaken as shy, nervous, or dishonest. They can be mocked, insulted, and even refused service. It is known to negatively affect employment.

I don’t remember the first time my voice decided to revolt, but I internalized it at a young age. I remember elementary school. We’re taking turns reading passages aloud from a book, but I’m not paying any attention to the speaker. No, I’m too busy counting the number of people ahead of me. I’m busy finding the paragraph I’ll have to die on. I understand every sentence and know every word’s pronunciation, but I’m not going to sound like I do. There are landmines along each paragraph’s lines. My peers stroll through their minefields unscathed. They don’t even realize how lucky they are. Each person finishing their paragraph is the tick of a clock counting down to detonation. My heartbeat intensifies. We call this anxious feeling of impending doom “anticipation.” It is as much a part of being a stutterer as the actual stuttering.

In middle school, sometimes my friends and I would hang out at the nearby library. Nobody had computers at home, so we surfed the web and played games on theirs. One day my friend showed me a website she made. It blew my mind. I didn’t know that we could make webpages. I found a new voice. The digital world became a place I could say exactly what I want to say. I use the web to make meaningful contributions to our conversations.

My stutter became milder with age, but it never went away. Situations we take for granted can make it more pronounced. Near the end of high school I got my first flip phone, and my analog struggles began entering the digital world. I started feeling excommunicated when businesses began using automated phone systems. I sometimes stutter when I have to say specific words without substitution, which makes speaking to the robots impossible. Then came Siri and Alexa, which frustratingly misinterpret pauses in speech as the end of a command.

Now it enters social media. Voice assistants are nice-to-haves, but social media is practically unavoidable for many people. Almost half of the people on the planet use some form of social media. Situations such as speaking in front of a group or talking on the phone can be particularly difficult for people who stutter. As social media moves toward real-time-voice, people with speech impairments will be disenfranchised in that new normal.

On the My Stuttering Life podcast, Pedro Pena recalls his first experience on Clubhouse. Pedro wants to ask one of his celebrity idols a question, but something happens: “Let me tell you, as I’m touching the hand icon to essentially raise my hand to ask a question, there was a physical change that I was experiencing. My heart was beating so hard, I was sweating, and I quickly un-raised my hand.” Pedro has been podcasting for more than two years, but the prospect of stepping up on stage in that voice-chat room triggers the all-too familiar tension, variable heart rate, and anxiety that people who stutter experience. I’ve had the same physical reactions. There have been situations where I’ve put my hand down and stayed in the audience due to the anxiety.

The sun still hasn’t risen, and I’m still in the audience of the #StopAsianHate Clubhouse room, when someone gets on stage to inflict pain on the community. He is swiftly booted from the stage. That may fly in most rooms, but not here. This is a safe space; a rare, inclusive room. I’m wrapping up my accounting work when a man named Joze starts to speak. I do a double-take. Someone else with a stutter, on here? Finally. I listen intently. He begins by assuring everyone that nothing is wrong with their devices. It feels like a regular part of his introductions. He has a severe stutter and works his way through every word. He applauds the room for speaking up and using their voices. He mentions he avoided speaking for almost his entire life “because of the stuttering.” It was only three years ago when he found his own voice. He is completely fluent when he sings. With the room’s permission, he sings a song that illustrates the challenges we face and the necessity of speaking up. The audience is speechless. There is so much praise. He returns to his regular voice. “Thank you. I’m done stuttering,” he jokes.

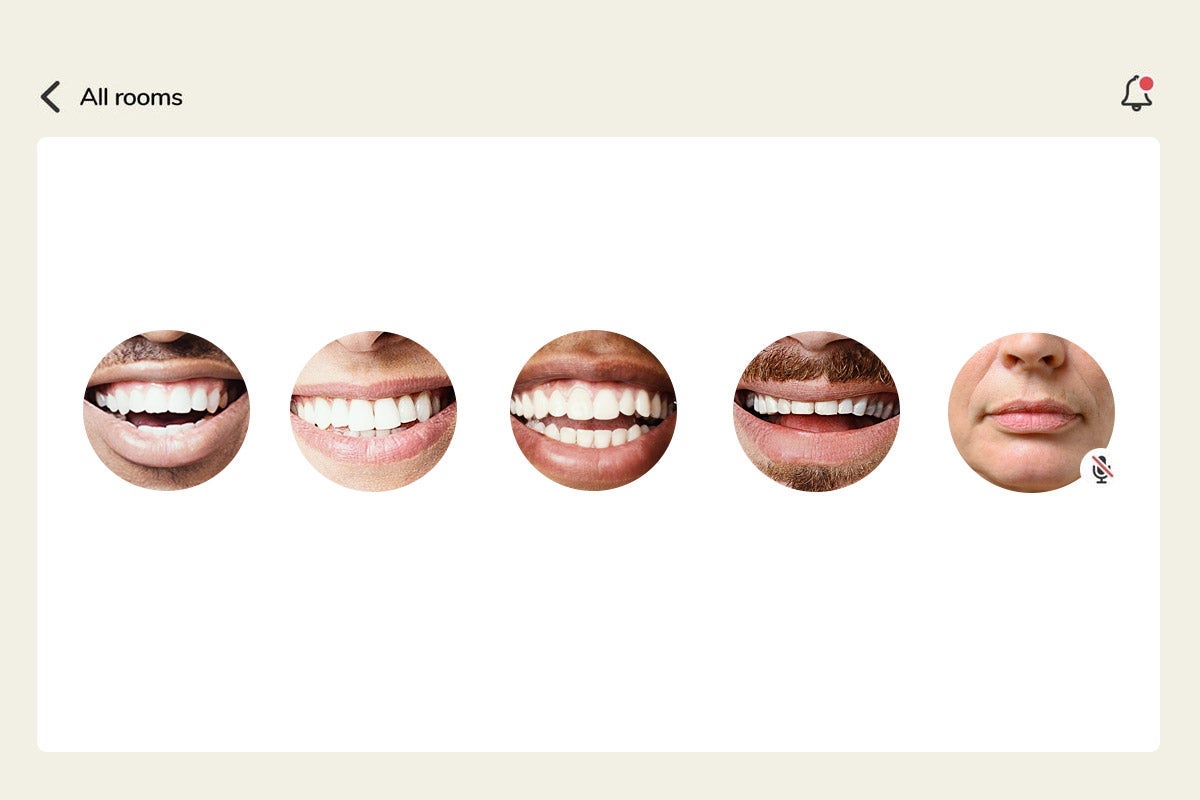

“What are the odds?” asks the room’s moderator. Clubhouse is estimated to have up to 10 million users and is growing exponentially. After signing up, I listened for several hours a week, but it was 49 days before I heard a fellow human with a stutter step onto the stage. In his podcast episode, Pena mentions he was only able to find two other stutterers on Clubhouse after searching. The stage selects for fluency and eloquence. Like a bad date, people are uncomfortable with any silence. For stutterers, the performance anxiety can be a gag.

Rachelle Dooley is a founder of Deafinitely Inclusivity, a Clubhouse club that hosts talks about how to be more mindful of those with disabilities. In addition to impacting her speech, her hearing impairment poses additional difficulties on the app. Her speech-to-text translator makes it hard to tell who is speaking and doesn’t always pick up every word. Unfortunately, she has been a victim of mockery and ridicule in some rooms.

Real-time voice chatroom platforms must make people with speech impairments feel welcome. If inclusivity remains an unsolved problem, then millions of people will be silenced.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.